I, (NAME), do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to regulations and the Uniform Code of Military Justice. So help me God.

In our busload of newly-sworn recruits, most have volunteered for the draft, to get their military obligation over with and move on with their lives. I have signed up mainly out of boredom, and once thought I might even put in 20 years and retire. Our training sergeants immediately begin working to break us down and resocialize us to army life, starting with the bus trip from the reception center to our new home in the E-company barracks. Sergeant Santiago is our host on the bus ride; he is a bantam-weight tyrant who does his best to terrorize us.

Civilian operating floor buffer, courtesy rentequip.org

After keeping our platoon awake until four in the morning hand-waxing the barracks floor to prepare for an inspection, our cadre of trainers have an idea – if we each pitch in $2, we can buy a used electric floor- buffer from a place they know of in town. They can get it right now; we can owe them until payday. We’re all for it of course, we don’t want to go through that again, and we buy a buffer that’s probably been sold to a dozen earlier training cycles.

courtesy thecmp.org

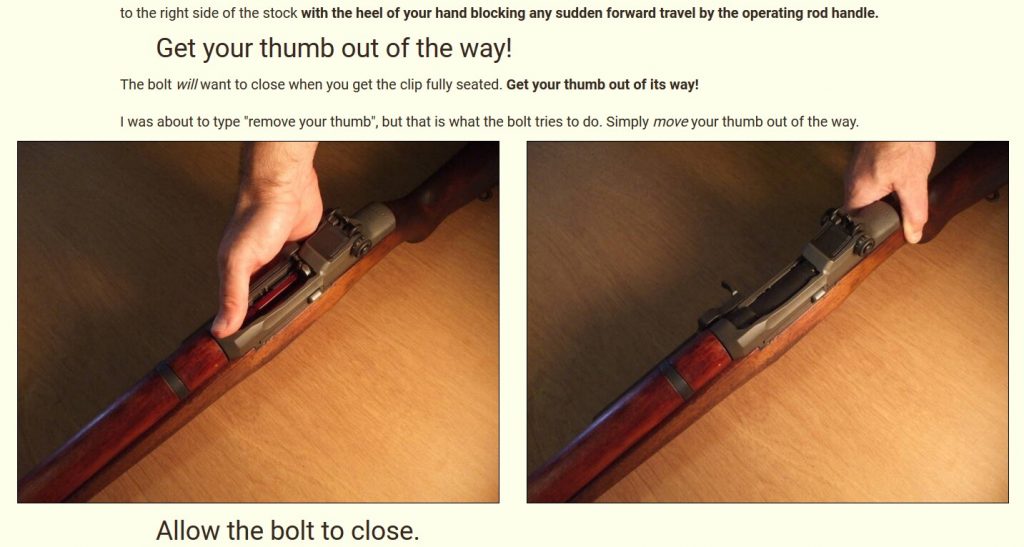

We learn to march, salute, and fire the M1 rifle, good fun that last one. However, I a become a victim of “M1 thumb”, a painful but temporary disfigurement.

Loading the M1 Garand rifle, courtesy m1-garand-rifle.com

During basic training we are out in the field for a week, sleeping in tents. During drill one rainy day, a few of us sneak off into a tent. Sergeant Johnson rips open the tent flap and threatens us with court martial and prison for “buggin’ out” of duty.

While drinking watered-down beer at the Post Exchange, we hear that one of our sergeants, a lifer, has just signed up for three more years. Since he seems otherwise normal, we ask him why. He asks where else could he get drunk and lose all his money every month, yet still have a place to sleep and three meals a day?

Our oldest sergeant is a grizzled Korean War vet. Overseeing our cleaning of the latrine, he spots a recruit trying to clean a toilet bowl while standing as far away from it as possible – with his scrub-brush extended, he looks like he’s fencing. His battle is with one particularly stubborn fleck of matter stuck tight to the porcelain. The sergeant reaches in and scrapes it off with his thumbnail. To the groans around him, he rhetorically asks, “Did j’ever see a pile of rotting corpses?”

Our oldest sergeant is a grizzled Korean War vet. Overseeing our cleaning of the latrine, he spots a recruit trying to clean a toilet bowl while standing as far away from it as possible – with his scrub-brush extended, he looks like he’s fencing. His battle is with one particularly stubborn fleck of matter stuck tight to the porcelain. The sergeant reaches in and scrapes it off with his thumbnail. To the groans around him, he rhetorically asks, “Did j’ever see a pile of rotting corpses?”

Some of us go on to Advanced Infantry Training, AIT, and a new set of sergeants and officers.

Sergeant Kolikowski gets word from home that his brother has been murdered. He goes to the battalion armory and signs out a M1911 .45 caliber pistol. He’s gone for a week, then returns and checks the weapon back in. Nothing is ever said about his absence.

We are taught to use the bayonet in offense and defense, no rules, kill or be killed. We drive it into a dummy, we pivot our rifles to bring a butt  stroke to a dummy chin, we thrust and parry. Sergeant Doherty doesn’t think I’m trying hard enough; he braces himself and shouts in my face, “Come on Smithee, try to kill me!” It’s hard to say why, but caught up in all the make-believe bloodshed, I make a genuine effort to kill him by stabbing him in the face. He’s prepared and fast enough to move out of the way, but it’s close, very close; he is surprised and calls for a smoke break.

stroke to a dummy chin, we thrust and parry. Sergeant Doherty doesn’t think I’m trying hard enough; he braces himself and shouts in my face, “Come on Smithee, try to kill me!” It’s hard to say why, but caught up in all the make-believe bloodshed, I make a genuine effort to kill him by stabbing him in the face. He’s prepared and fast enough to move out of the way, but it’s close, very close; he is surprised and calls for a smoke break.

A few days later, he tells me I’m going on a work detail with him. Several of our barracks’ light bulbs are burned out, and it’s not easy to get replacements for such things in the army. Our mission is to drive a borrowed Jeep over to a currently vacant barracks and remove its light bulbs. Despite what his name would suggest, Sergeant Doherty is black, and I think my presence is partly to inoculate him from suspicion when visiting an empty barracks. Or, maybe he just wants the company, I don’t know. We stride in looking like we are on official army business; we gather a good number of bulbs; we leave. Mission accomplished.

One day our company commander gathers 20 or so recruits into what we might today call a focus group. It is surprisingly touchy-feely, and at one point he asks if there are any problems he should know about. It’s not like me to pass up an opportunity to complain, and I raise my hand and say there are two problems I know about, a small one and a larger one. I give the trivial one first – during breakfast, the sugar dispensers run out and don’t get refilled, so the second half of the company to arrive has no sugar for their coffee. The larger problem is that we are not getting enough to eat; half the time we leave the mess hall still hungry. He asks if anybody else feels the same way; almost every hand goes up. Looking angry, he promises to look into it.

Here I’ll mention something I saw once when on KP (kitchen police: cleanup and other grunt work), and didn’t give any thought. A civilian truck pulls up behind the mess hall and the cooks load on 8 or 10 bulk food items; a case of canned peaches is one that sticks in my mind.

In a few days there’s plenty of food, more than plenty, the servings overload our trays. The scam that scammed too deeply has been ended. As I dump almost half a chicken into the garbage can, the mess sergeant asks me sarcastically if I’m getting enough to eat.

In a few days there’s plenty of food, more than plenty, the servings overload our trays. The scam that scammed too deeply has been ended. As I dump almost half a chicken into the garbage can, the mess sergeant asks me sarcastically if I’m getting enough to eat.

Comments are closed.