So, here’s the deal with my father. He was a union housepainter, paper hanger and sometime bartender. He was a working drunk who eventually let everyone down. He had a barfly girlfriend named Millie with whom he had a bastard child. In the polite euphemism common among amateur genealogists seeking disappeared fathers and uncles, he “left the family”, his wife and two sons, in about 1944.

His half-sister, my Aunt Frances, made room in her home for my mother and me; his sister, my Aunt Elizabeth, made room for my brother. I think they felt a family guilt for what he had done. His sisters still loved him, and if they spoke of him at all, they mentioned his terrific sense of humor.

Although habitual drunkenness is said to be a genetic predisposition among the Irish, I don’t think genetics are a good excuse. I think habitual drunkenness is a character flaw, a weakness that can be overcome by power of will, or nowadays by psychiatric treatment. You’ll probably see a mix of love, anger and disappointment in what I’ve written here.

He was born in 1903 in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City, in a tenement two blocks behind Lincoln Center before there was a Lincoln Center. I don’t know anything about his early life, but as poor Irish, I’m sure it was not easy.

His father’s given name was Bernard, and he lost out to my mother when he wanted to honor the Irish tradition of naming me after my grandfather. Although on paper he lost that fight, at home or away he never called me anything but Barney. His own name was George, but only his sisters called him George. All his friends, and my mother too, called him Pardo. Where that name came from or what it meant is lost to the ages.

He worked for Haas, a big painting contractor, and was a rabid union man. My Uncle Jim, Aunt Frances’s husband, had a successful one-man, one-panel-truck, non-union painting and decorating business. My father called him “Your scabby uncle Jim”, notwithstanding that my mother and I were living under Uncle Jim’s roof at the time.

He could be hurtful: my brother went to vocational school, which my father for no good reason called “dummy school”.

He was generous with money, and I once heard my mother say that while he was buying “drinks for the house” his family was being shortchanged. I always think of that, and say “Nothing for me, thanks” when some stranger in a bar wants to be a bigshot.

Here are a few memories from when my parents were still together:

One Sunday morning I sit on his lap helping to hold the paper while he reads aloud The Katzenjammer Kids comic page, speaking the words of Hans, Fritz, Mama and der Captain in a vaudevillian German accent. He is laughing and delightful; this is my happiest childhood memory. But my mother is not amused, she keeps trying to tone him down, I never understood why. Maybe he was still drunk?

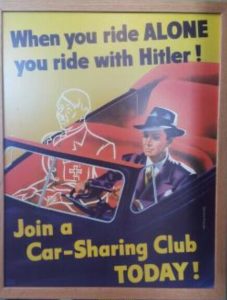

He has a loud argument with an air raid warden who claims he can see light leaking from an upstairs window during a WWII blackout. My mother somehow settles it before the authorities need to be called.

I am playing a block away from our house one afternoon when I see my white-shirted father walking up the block to go to his bartending job. I chase after him, hysterical because he hasn’t said goodbye. When I catch up, it isn’t him, he hasn’t left, but I cry even harder.

I open the front door to a salesman who asks to speak to “your mommy”; I inform him that she’s in bed with my daddy. The grownups find this story very amusing, not sure why at the time.

After he left us, he would sometimes arrange with my mother to take me for a day or so:

He and one of his buddies made a deal with the absentee owner of a house at the shore. They would paint it in exchange for a week’s free stay during the summer. I stayed with them for the few days they were painting. When the owner stopped by, she saw me helping to paint and asked if I was working hard. I repeated the expression I had heard them use many times, “Just slappin’ it on”. While we were there my father took me grocery shopping. Already a slave to radio advertising, I begged him to buy Cheerios; he said I wouldn’t like them but I argued and nagged and insisted, and we came back with Cheerios. The next morning, he served me a bowl of Cheerios and milk and they were nasty, just plain cardboard, nothing like the honey-nut stuff you spoiled kids have today. Giving credit where credit is due, he didn’t make me eat them.

When I was about eight, we went driving in the country with his girlfriend and her two kids, a boy about six and a girl about four, me generally ignoring the three of them. We stopped at a roadside custard stand with a few metal chairs in front. I was still ignoring them when I heard the boy shout “Mom! Sissie’s peeing!” I look over and Sissie is standing atop a chair, urine running down her bare legs and all over the seat. I take a close look at Sissie for the first time and, even to my own young eyes, she has what we recognize today as acute Down syndrome. Much later in life I realize that Sissie, who was eventually placed in the Vineland Training School, is my half-sister. When two drunks make a baby, it may not turn out well.

He would bring me with him to a favored workingman’s bar that had a free lunch, an elaborate spread of cold cuts and just about everything else. To drink, he favored boilermakers, which is a shot of whisky followed immediately by a glass of beer. I usually drank sarsaparilla.

He had lots of friends and acquaintances in the bars. Once he introduced me to a friend the right side of whose face looked like a lopsided, swollen strawberry. He later explained that the friend was a mustard gas victim from WWI. Oh, I see. On the bright side, another friend would salt the phone booth coin returns with nickels, then say, “Hey Barney, why don’t you go see if anybody forgot their change?”

He and some of his painter buddies shared a double room in a workingman’s hotel in downtown Newark.

My tasks at the hotel were to go to the diner next door and pick up takeout coffee, or to buy cigarettes. A cigarette purchase consisted of simply putting a quarter into the machine and pulling a knob, usually the one under the Chesterfields. Each pack of cigarettes included a few pennies sealed inside the wrapper as change from the purchase. These pennies were treated as a nuisance and tossed into a soup bowl kept on the windowsill.

When the painters go off to work in the morning, I am left to my own devices. I’m sure my mother knew very little about what went on when I stayed with my father, and she never quizzed me about whether his girlfriend was present (she usually wasn’t) or any other aspect of my visits. I was pretty much what they call today a free-range child. Unsupervised children were not uncommon then.

I would take a handful of pennies from the bowl and bring them to the game arcade a block or two away on Mulberry Street. The hotel room was on perhaps the fourth floor, directly above a green canvas awning. The awning had a swoop to it, and a penny properly dropped would shoot out into the street. I made a mistake in timing once and hit a car as it was coming by; the driver got out, looked up and cursed me. I guess he had seen me leaning out the window from up the block.

One night the painters put down a blanket in the next room and shoot craps. My father has to tell them to watch the language.

At the Painters Union annual picnic (his girlfriend is there), I take it upon myself to set up pins on the outdoor skittles-bowling lane. It is fun and I am good at it. Later I help out by running cups of beer and sarsaparilla between the outdoor bar and the table. I discover I like the taste of beer and get my first buzz on.

At the lunch counter in Newark Penn Station one morning, my father passes out and ends up on the floor. There are two firemen sitting on the other side of the U-shaped counter. I go to get them but they won’t help. Maybe they knew something I didn’t? After a while he revives on his own.

On a different day in the station, I get my arm trapped fooling around with the meshing bars of an exit turnstile. A mechanic sets me free.

One day we go to a tailor shop, where I am fitted for a suit. I get to pick it, and I choose a traditional style, in gray. The deal includes a hat, and I go with a Jack-Lemmon-style businessman model. When I get home my mother likes the suit, and says that the color is called “salt and pepper”, which to me sounds kind of dumb. She checks the label, and says “Hmm, reprocessed wool”, which years later I learn is thought to be of inferior quality. I wear the suit next day to Sunday School, where I get ragged on for being overdressed, but mostly I get ragged on for the hat. I never wear it again.

Somewhere around this time he brings me to an indoor three-ring circus, maybe at Madison Square Garden. We are only four rows back from the action. There’s a clown with a bucking donkey, and part of his act is challenging anyone in the audience to ride the donkey. I stand up to volunteer, but my father puts the kibosh on that idea. Maybe it’s because I’m wearing my suit.

The circus sells pet “chameleons”, really just anole lizards that they collect during the off season in Florida. As sold, the creature has a thin chain around his neck that attaches to your clothing, then he just uses his native abilities to stay stuck to wherever you put him. My mother was not thrilled.

When I am about ten he calls my mother to invite me to a Yankees game. The trip is sponsored by the Eagles, an Elks-like social club for people of the Polish persuasion. I think most of his buddies in the painters union are Poles, e.g. his friend “Stash”, so he’s probably an honorary member. The day before the Yankees trip, he picks me up at home (probably using Stash’s car, he never owned one as far as I know) and we go to his room across the street from the Eagles lodge. There is a trundle bed for me. Millie comes by, then later his landlady. When I am introduced to the landlady, she says “I bet you’re happy to see your Aunt Millie.” I am both astounded and insulted, and say “SHE’S NOT MY AUNT.” Maybe I have confirmed something the landlady already suspected?

The next day the Eagles load up their chartered bus. Late arrivals make for a late start, then traffic is bad and we run into long stretches where the bus doesn’t move at all. There is beer on board, and after a while the call goes up for a bathroom break. The driver pulls over as far as he can and everyone gets out. My memory of this is of 10 or 12 men leaning with one hand against the right side of bus, taking a wide stance, feet well back, as they piss in concert against the bus or half-under it. To anyone who doesn’t know better, it looks like they are trying to push the bus over on its side.

When we finally arrive at Yankee Stadium it’s the 7th inning.

Once we are seated, I discard any notion of catching a foul ball, for our deck is deep under an even higher deck, and we are far back from the third-base line. In fact we are more just on the third-base side of the park. We are seated in two rows, me in the second, where I observe. There is more beer, and the Eagles pass pint bottles of whisky or such back and forth. I have a hotdog, soda, Crackerjack and a souvenir program. All-in-all, it’s a dismal experience.

He phoned my mother one more time to invite me somewhere a few months after the Yankee Stadium fiasco. That day had been sort of a last straw for me and I said “No” and never saw him again until he was dead.

My brother maintained a relationship with him to some degree, occasionally running into him in Bloomfield.

One Saturday afternoon years later, I had been out of the house for several hours when my wife received a phone call from Newark City Hospital. They wanted to know what she wanted done with Mr. Smithee’s body. My wife hadn’t thought about my father in years, and it took a few frightened moments to establish that the deceased Mr. Smithee was not me, but my father. His body had been in the morgue for a week.

Cause of death? He got mugged, or fell down his apartment stairs, or maybe a little of both, I don’t remember. In the big picture I guess it doesn’t matter.

Over the years, my mother had kept up a small death-benefit policy from Prudential. Our Bloomfield relatives handled the arrangements. It was the same funeral home Uncle Jim was buried from.

For the funeral director I set aside clean underwear and socks, a shirt and tie, and my second-best suit. It was the least I could do.

There wasn’t much of a turnout except for his family.

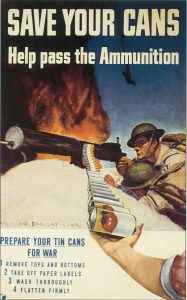

chair. Back then, cans were made of tin-plated steel, not the cheesy aluminum they use today. In my teen years, it was a benchmark of strength to be able to fold a beer can in half with just one hand.

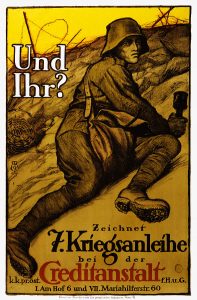

chair. Back then, cans were made of tin-plated steel, not the cheesy aluminum they use today. In my teen years, it was a benchmark of strength to be able to fold a beer can in half with just one hand. How I fought Hitler, part 2 – Here is a link to my recollections of

How I fought Hitler, part 2 – Here is a link to my recollections of