These are some police encounters/interactions that I’ve had over the years. I hope this piece doesn’t come off as anti-cop; I’ve had many positive encounters with the police along with the negative ones, which are easier to remember. Society needs cops, and I am the first to call for the water cannon during large-scale bad behavior.

I wish I could say “at least I never got arrested”, but a scam in Clarksville, Tennessee spoiled my record. The cops there were only doing what the town demanded of them: bringing in more revenue.

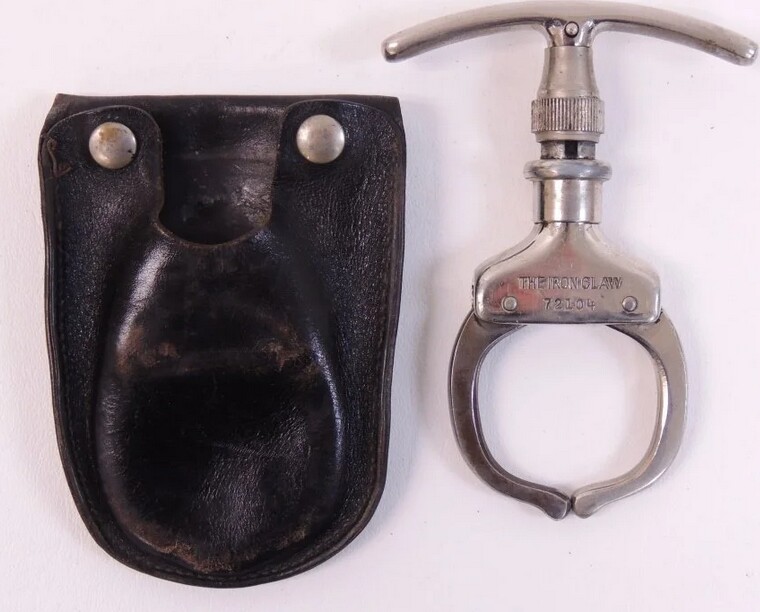

Iron Claw Wrist Cuff with leather holster, courtesy liveauctioneers.com)

At about eight years old, I was in Newark Penn Station with my father, who was talking to a cop. I don’t know who initiated the conversation, but I doubt it was my father. More likely, the cop came over because his Spidey-senses spotted a drunk. I didn’t pay any attention to what they were talking about, but while they talked, I studied the cop’s holster and gun, and the other equipment attached to his belt. I asked him what the thing with the handle was for. I don’t remember if he told me, but he did show me, right there in front of my father.

The Iron Claw Wrist Cuff has a locking ratchet; when the handle is pulled up, the claw gets tighter. The only pictures I have seen of the claw in action show it as a come-along restraining device encircling the subject’s wrist. However, the demonstration I received was of an “off-label” use, as a tool of torture. In this usage, the claw is closed on the wrist like a letter C, with one arm of the claw closing down on the upper side, between the radius and ulna bones, and the other arm digging into the pressure point underneath. Try grabbing one wrist with your other hand, fingers on top, tip of the thumb digging in hard underneath. Hurts, doesn’t it? Now imagine that grip made of steel. Oh, and the claw’s handle can be twisted sideways for increased pain. All in good fun, just showing this kid how it works. Hug your babies tonight, officer. Hope you enjoyed it.

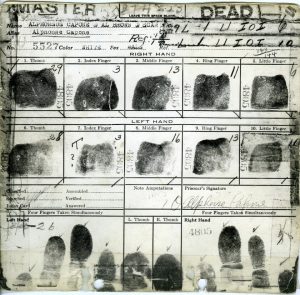

When I was in Cub Scouts, at maybe nine or ten years old, they took our pack on a field trip to the Bloomfield Police Department; it might have been East Orange but I’m pretty sure it was Bloomfield. In particular, I remember they showed us the cells; I believe there was an implied threat there of what could happen if we were not good citizens. They also took our fingerprints, sort of an interesting process to watch back in the days before you could see it done on TV twice a week. They made and retained for themselves a set from each of us. The reason they gave was “In case you get lost”, but what they really meant was either, “In case you are ever so hideously mutilated that you are unrecognizable”, or, more likely, “In case you grow up to burglarize the house of somebody important enough to warrant a full investigation”. A few years later I mentioned the fingerprinting to someone who said, “Oooo, FBI knows who you are now, better not do anything!”, implying that I might be the type to maybe “do something” some day. The army took my fingerprints too, so I guess the FBI has a double set.

One 4th of July, my high-school buddies and I had some firecrackers, nothing big or dangerous, just those little ones about two inches long that come strung together in a pack of 50 and go “bang” loud enough to make anyone who is unprepared jump. We were setting them off on the curb in front of my house, sometimes putting one under a tin can to see how far it would fly. We only had one or two packs, so we lit them one at a time to make them last.

(When we were younger, we lit them with slow-burning “punks”, skinny foot-long sticks of compressed sawdust, but there was no need for punks this year, since at least one of us always had a cigarette going.)

Anyway, one of the neighbors, probably the constant complainers from two doors down, called the police. When they arrived, one cop explained (as if we didn’t know) that fireworks were dangerous and illegal, and that they had to confiscate ours and “destroy” them, that’s the word he used. I have to give them credit – they destroyed our firecrackers right then and there, by driving two doors down the street, lighting the whole string at once, dropping them into the gutter and driving away.

I got a speeding ticket on Park Avenue in East Orange when I was 17; I know I was 17 because one condition to resolve the ticket was that I bring a parent to court so the parent could receive a lecture also. My mother was annoyed at first, but changed her tune when “The judge looked just like Gregory Peck!”

The Glen Ridge police once gave me a speeding ticket for doing 38 in a 35 zone on my way to work. Glen Ridge didn’t want kids driving crappy old cars through their classy town.

Traffic stop, courtesy law offices of Hart J. Levin

Other classy towns that didn’t want kids driving through were the Caldwells, several towns in North Jersey. We would cruise around the area aimlessly, then maybe stop for burgers. One night we were driving around, four kids in the car, not speeding or anything, when the cops pulled us over. They explained there had been a warehouse break-in and burglary in the next town, and the night watchman had been knocked out. They asked what we were doing in the area and made us get out of the car so they could look us over. There was no search. They were satisfied and let us drive off. Next night, different car, different guys (except for me) out cruising in the same area, stopped by the same two cops. One comes up to the window and explains about a break-in and burglary in the next town, night watchman got knocked out. I asked him if it was the same night watchman that got knocked out the day before. They took a closer look at us, then said to keep moving. No apology was offered, and we didn’t expect one.

My friends and I generally hung out on the corner by Vince’s grocery store. Vince’s neighbors were mostly our own parents, aunts and uncles, so there were few objections to us being there. Some neighbors did object, though. One of them was Angelo, a special cop who lived on the second floor of the building next door. He had a new baby, so he was stretched pretty thin, and wanted us to keep the noise down. I don’t think we were ever noisy; it was just conversation; the boombox hadn’t been invented yet.

One day Angelo came out on his porch and shouted down to us to be quiet, adding that he was a cop. I knew he was only a special cop, and muttered “Let’s see your badge”, more as an aside to the group than directly to him. He went back inside, and a moment later was downstairs, walking up to me with a .45 automatic. He cranked the slide and pointed it in my face from about two feet away, saying “THIS is my badge. Now get out of here!” That was a tough argument to counter, so I turned around and started walking home, followed shortly by everyone else. I still remember how big the hole in the front of that thing looked from up close. I don’t know if Angelo ever got hired as a real cop, but I hope not.

When I worked at Foodland, employees were expected to keep an eye out for shoplifters. If we saw someone leaving without paying, we were supposed to intercept them, then bring them back inside to sign a confession form in which they promised never again to enter the store. I didn’t try very hard to catch any, but one Sunday I spotted a particularly egregious case. Right in front of me, without even looking around to see if anyone was watching, a fiftyish woman picked up a chunk of expensive cheese and put it into her purse. I approached her as she was leaving the store, told her I knew what she had taken and asked her to follow me back to the office. (Looking back, I am ashamed of being involved in this apprehension program. I wasn’t trained as a police officer. If stores have a shoplifting problem, they need a paid security guard walking the aisles to deter it, not employees stopping people outside after it happens .)

She ignored me and kept on walking. Stupidly, I grabbed a nearby clerk and told him to come with me. I didn’t have a plan – we just followed her, with me occasionally entreating her to come back to the store. So, here’s the picture, a woman of a certain age wearing a Persian-lamb coat is being followed closely down the sidewalk by two young men wearing supermarket whites. My lack of a plan was resolved when a police car took interest, and after hearing our stories brought all three of us to the police station. After some conflicting explanations, the woman and I were eventually given a court date, a Thursday. When I explained to my bosses where I’d be the next Thursday, they said I’d have to take Thursday as my day off; in other words, they weren’t going to pay for my court time. I said in that case I wouldn’t testify, and they said that was fine. The punchline? My shoplifter turned out to be the aunt of one of the owners.

Driving home from work one Sunday evening, I was pulled over while headed north on Route 9 in Elizabeth. I had a ’51 Lincoln at the time, which at nine years old looked more like a hoodlum car than a luxury one. I had no idea why I was stopped. The officer, an older gent, asked if I knew the speed limit there; I replied 45 and he said no, it’s 35, but you were doing 45 exactly. I think he liked that at least I was observing my own imaginary speed limit, and for extra credit was wearing a white shirt and tie. He let me go with a warning.

Driving home from work one Sunday evening, I was pulled over while headed north on Route 9 in Elizabeth. I had a ’51 Lincoln at the time, which at nine years old looked more like a hoodlum car than a luxury one. I had no idea why I was stopped. The officer, an older gent, asked if I knew the speed limit there; I replied 45 and he said no, it’s 35, but you were doing 45 exactly. I think he liked that at least I was observing my own imaginary speed limit, and for extra credit was wearing a white shirt and tie. He let me go with a warning.

One Sunday morning future wife and I were headed down Park Avenue in East Orange. It was early, traffic was light, and I was speeding. From a long block away, I spotted a cop on traffic duty, standing on the corner in front of a church. I tried to slow down, but not soon enough, and he stepped into the road to flag me down. Oddly, he was wearing motorcycle boots and the whole strap-across-the-chest deal, but seemed to be on foot. He walked up to the window and I rolled it down. As soon as the window was down, future wife leaned across me and demanded, “Where’s your motorcycle?” Oh shit, I thought, this isn’t going to end well. He replied something like, “Oh, hi there!”, and went on to explain to her that he had had an accident with his motorcycle, and while he was recuperating he was on traffic duty. “Damn!” I said as we drove away. “You know everybody.”

For the sake of completeness, I’ll mention the NYPD subway cop who refused to give me directions when I asked him the same question, at the same location, two days in a row. His response, “Same as I told you yesterday”, is a perfect example of New York City attitude; it runs deep in the blood and I can’t fault him. In fact, I don’t bear a grudge against anyone mentioned here, except for that one sick bastard who used the iron claw on an 8-year-old.

When I was growing up, we generally had a cat in the house. I don’t know where we got them or to which of us they belonged; if a cat can “belong” to anyone, probably to my grandmother.

When I was growing up, we generally had a cat in the house. I don’t know where we got them or to which of us they belonged; if a cat can “belong” to anyone, probably to my grandmother.